Special Schools dedicate so much time and resource to ensuring their provision truly meets the…

The New Ofsted Criteria and Work Scrutiny

Prompted by the new focus on the Quality of Education and in particular the intent, implementation and impact of the curriculum, Ofsted have now published a document ‘Inspecting education quality: workbook scrutiny’.

Background

Workbook scrutiny is seen as a contributory element, amongst many others, towards judging the quality of education.

As part of ensuring a standard and consistent approach to inspections, Ofsted developed and piloted a number of indicators (assessment criteria), some of which they tailored to workbook scrutiny.

These were piloted by nine HMI, with a mixed range of subject expertise, to see if they were useful and reliable. As part of the trial they scrutinised books which were within and outside their area of expertise and each scrutiny was undertaken by at least two inspectors.

In developing the indicators, a wide range of research literature was consulted and the final four were finalised with the following criteria in mind:

- the aspects of the quality of education described in the indicators should be observable in workbook scrutiny;

- the indicators should cover different aspects of the quality of education, for example:

- what is taught and learned (the breadth and depth of subject-matter content);

- how subject matter is taught and learned (from the perspective of how learning is structured to allow for efficient and meaningful acquisition of new knowledge);

- whether and how pupils consolidate knowledge so that it remains in their long-term memory.

The four chosen indicators were:

Building on previous learning

Pupils’ knowledge is consistently, coherently and logically sequenced so that it can develop incrementally over time. There is a progression from the simpler and/or more concrete concepts to the more complex and/or abstract ones. Pupils’ work shows that they have developed their knowledge and skills over time.

Depth and breadth of coverage

The content of the tasks and pupils’ work show that pupils learn a suitably broad range of topics within a subject. Tasks also allow pupils to deepen their knowledge of the subject by requiring thought on their part, understanding of subject-specific concepts and making connections to prior knowledge.

Pupils’ progress

Pupils make strong progress from their starting points. They acquire knowledge and understanding appropriate to their starting points.

Practice

Pupils are regularly given opportunities to revisit and practice what they know to deepen and solidify their understanding in a discipline. They can recall information effectively, which shows that learning is durable. Any misconceptions are addressed and there is evidence to show that pupils have overcome these in future work.

(*see findings below for implications).

What the Trial Found

There is further work to be done in developing the indicators and descriptors.

Inspectors found that the indicators:

- were helpful particularly because they created a focus on “what pupils are actually learning, instead of elements such as marking, handwriting or neatness, etc”;

- made it easier to make judgements for subjects both within and outside their area of expertise.

Reliability was seen to be higher at primary school than at secondary school level. The supposition was that subject knowledge required of secondary pupils is likely to be deeper and more specific, and therefore the subject expertise of the “scrutineers” also needs to be greater in the secondary sector.

Reliability was also seen to be high for the first three indicators, ‘Building on previous learning’, ‘Depth and breadth of coverage’ and ‘Pupil progress’ but less so for ‘Practice’.

Focusing workbook scrutiny (as well as lesson observations) across a single subject/department/year group is helpful in securing greater validity and reliability. This is because some subjects (for example history in primary schools) may not be taught every day or may not be taught to different year groups on the same day.

It is important to note that in the trial the workbook scrutiny took place in isolation – out of school. Thus, the process was different from how it will be in live inspection, where workbook scrutiny will complement conversations with leaders and pupils, as well as lesson observations, in checking that the quality of pupils’ workbooks matches leaders’ curriculum intent.

Looking at the indicators it is relatively easy to see why reliability was not high for “Practice”. The description contains elements which would be difficult to evidence through scrutinising books in isolation.

Further Issues Identified by the Pilot

- Workbook scrutiny may not be possible to implement in special schools. Those schools may not use workbooks as pupils’ work and progress may be captured in a different way (such as through post-it notes or videos).

- Workbook scrutiny may also not be applicable to further education and skills (FES) settings. Students in this sector may not typically be required to bring in their work to classes (for example sixth form pupils), and the main written activity during lessons may be note-taking.

- Pupils’ work may look different in schools that use alternative methodologies in teaching and learning (for example Montessori schools) and may not necessarily be captured in workbooks.

- Modern foreign languages may not lend themselves as easily as other subjects to workbook scrutiny because a lot of classroom activity could be spoken rather than written.

- The amount of work in workbooks at the beginning of an academic year (for example in September, October and possibly November) may not be sufficient for inspectors to make a valid and reliable judgement about curriculum and learning progression.

Summary

Our view is that workbook scrutiny in school will always be more valid if conducted as part of an inclusive, rounded monitoring process.

For example, a lesson observation followed by a workbook scrutiny where pupils are involved in discussing their work will give much greater information about the quality of education (teaching) and the impact of the curriculum over time than one isolated monitoring event. This also gives context to the scrutiny or the observation. Ofsted call this “triangulation”.

It is vital that schools keep workbooks from the last few months of a previous academic year for pupils still in the setting. This will give clearer evidence of impact over time for curriculum innovation and teaching development strategies.

The main points for schools to address are:

- If developing you own work scrutiny proforma, ensure that there is a clear focus on “what matters” – evidencing the quality of education: teaching, learning and the impact of the delivered curriculum.

- Don’t carry out a work scrutiny as a standalone task. Always piggy-back it with other monitoring activities such as observation or pupil conversation.

- Ensure subject leaders, and other staff involved in any scrutiny, have the requisite subject knowledge and expertise to be able to make informed judgements.

- Ensure that any work scrutiny results in analysis, feedback and a plan for any further action if needed. Where possible, involve those staff whose books have been looked at in any planning discussions.

For further information on the new Ofsted Education Inspection Framework, see our blogs ‘Meeting the New Ofsted Criteria for Lesson Observation’ and ‘4 Points to Note About the New Ofsted Framework’.

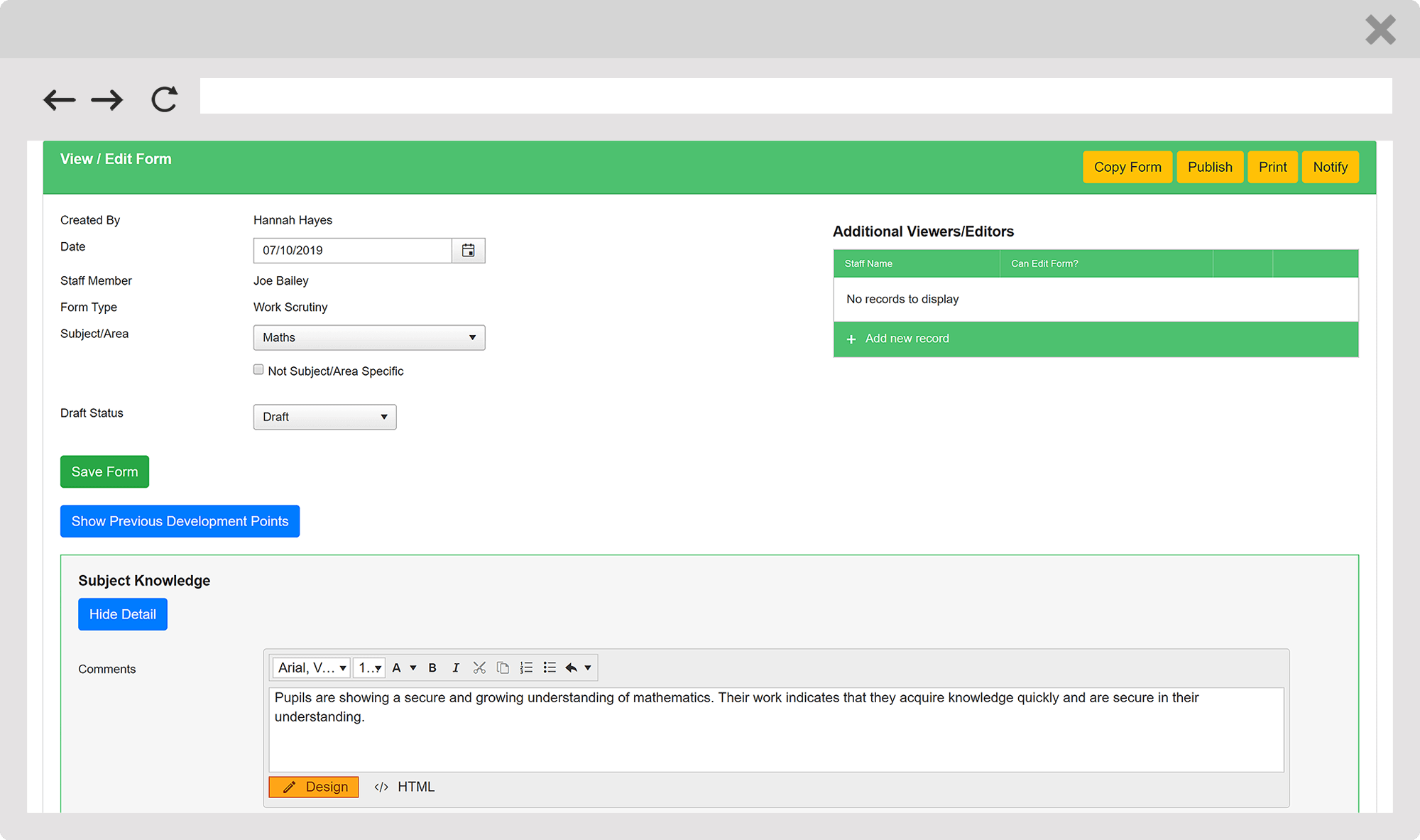

Our Online Tool for Recording and Analysing Work Scrutiny

However you choose to carry out your work scrutiny or book looks going forward, our online tool can help you record and analyse them with ease. Forms can be custom built to match your own framework, or you can choose to use our comprehensive framework which incorporates the new Ofsted criteria.

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

[…] Work scrutiny of books or other kinds of work produced by pupils who are part of classes that have also been observed by inspectors. Inspectors should review a minimum of 6 workbooks in lessons they visit and scrutinise work from at least 2 year groups in depth. They will be guided by ‘Workbook scrutiny – Ensuring validity and reliability in inspections – Ofsted June 2019’ (which we blogged about here). […]